How Captain Kirk Led Me to Historical Fiction

It was Star Trek that got me interested in historical fiction. Not because I’d been watching the crew interact with historical figures on the holodeck—the Next Generation didn’t exist when I was a kid. And it wasn’t because Kirk and Spock once met a simulacrum of Abraham Lincoln. It was because, Star Trek nerd that I was, I’d read that Star Trek’s creator Gene Roddenberry had modeled Captain Kirk after some guy named Horatio Hornblower. I didn’t think I’d like history stories, but I sure liked Star Trek, so I decided to take a chance. Once I rode my bicycle to the library and saw how many books about Hornblower there were, I figured I’d be enjoying a whole lot of sailing age Star Trek fiction for a long time to come.

It was Star Trek that got me interested in historical fiction. Not because I’d been watching the crew interact with historical figures on the holodeck—the Next Generation didn’t exist when I was a kid. And it wasn’t because Kirk and Spock once met a simulacrum of Abraham Lincoln. It was because, Star Trek nerd that I was, I’d read that Star Trek’s creator Gene Roddenberry had modeled Captain Kirk after some guy named Horatio Hornblower. I didn’t think I’d like history stories, but I sure liked Star Trek, so I decided to take a chance. Once I rode my bicycle to the library and saw how many books about Hornblower there were, I figured I’d be enjoying a whole lot of sailing age Star Trek fiction for a long time to come.

Of course, it didn’t turn out quite like that. Hornblower wasn’t exactly like Kirk, and his exploits weren’t that much like those shared by the crew of the Enterprise, but they were cracking good adventures. Thanks to my own curiosity but mostly to the prose of the talented C.S. Forester, my tastes had suddenly, and accidentally, broadened beyond science fiction. I’d learned that other flavors of storytelling tasted just as good.

Of course, it didn’t turn out quite like that. Hornblower wasn’t exactly like Kirk, and his exploits weren’t that much like those shared by the crew of the Enterprise, but they were cracking good adventures. Thanks to my own curiosity but mostly to the prose of the talented C.S. Forester, my tastes had suddenly, and accidentally, broadened beyond science fiction. I’d learned that other flavors of storytelling tasted just as good.

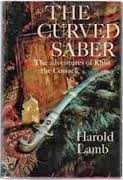

I no longer thought of historical fiction as a strange, untouchable world, and as I grew older I tried more and more of it, sometimes because a period interested me and sometimes just because I liked a cover or a title. That’s how I found the work of Cecilia Holland, and it’s why I wasn’t afraid to try out a book by Harold Lamb titled The Curved Saber after I was spellbound by Lamb’s biography of Hannibal, the great Carthaginian general. (I’d read it for a high school research paper.) I’d read Fritz Leiber’s Lankhmar stories by then, and recognized Harold Lamb’s Cossack tales were a related animal. In an introduction to one of Harold Lamb’s books, L. Sprague de Camp mentioned dozens of Lamb’s stories had never been reprinted. I never forgot that statement, although it was years before I decided to look into the matter. After all, if no one had bothered to collect them, how good could they be?

Really good, as it turned out. So good that my hunt for them felt a little like a search for lost artifacts, difficult to obtain, but gleaming with promise. Lamb’s stories were hard to find because they existed only in rare, yellowing pulp magazines, owned only by collectors or a handful of libraries scattered over the United States. The more of Lamb’s stories I read, the more interested I became not only in his fiction, but in the pulp historicals in general. Maybe it shouldn’t have surprised me that the kind of heroic fantasy fiction I’d come to love sounded so much like the best of the pulp era historicals. These were the stories in the magazines when sword-and-sorcery founders Howard, Leiber, Moore, and Kuttner were coming of age. We know from Robert E. Howard’s letters that he purchased the most prestigious of these historical pulp mags, Adventure, regularly, and that he loved the work of a number of authors who were printed regularly in its pages.

Really good, as it turned out. So good that my hunt for them felt a little like a search for lost artifacts, difficult to obtain, but gleaming with promise. Lamb’s stories were hard to find because they existed only in rare, yellowing pulp magazines, owned only by collectors or a handful of libraries scattered over the United States. The more of Lamb’s stories I read, the more interested I became not only in his fiction, but in the pulp historicals in general. Maybe it shouldn’t have surprised me that the kind of heroic fantasy fiction I’d come to love sounded so much like the best of the pulp era historicals. These were the stories in the magazines when sword-and-sorcery founders Howard, Leiber, Moore, and Kuttner were coming of age. We know from Robert E. Howard’s letters that he purchased the most prestigious of these historical pulp mags, Adventure, regularly, and that he loved the work of a number of authors who were printed regularly in its pages.

After years of research I came to conclude something that was obvious in retrospect: fantasy and historical writers had been cross-pollinating for a long time. More recently, authors like Guy Gavriel Kay and George R.R. Martin have been writing acclaimed works at least partially inspired by real world cultures and events. And some writers have been blending fantasy and history. We don’t have to look too much further than Howard’s stories of Solomon Kane or C.L. Moore’s tales of Jirel of Joiry to see that genre mash-ups have been going on for a half century, but we can journey even further back to Beckford’s Vathek or even into the mythlogized cultural history of the Persian Book of Kings (the Shahnameh) or the Iliad and the Odyssey and see that genre divisions didn’t used to exist.

Our society’s currently experiencing a resurgence of interest in historical movies, and I can’t help noting that films like The Centurion or The Eagle were marketed very much like fantasy action movies; few would argue that 300 was targeted to hit the same demographic that had enjoyed the battle sequences from the Lord of the Rings trilogy. It might be that today’s audiences are more savvy than I was as a young man, and that the blending of genres we’ve seen over the last decade has broken down the barriers that once kept historical fiction readers apart from fantasy readers apart from science fiction readers and so on. I’d certainly like to think so. Maybe none of us, readers, writers, or viewers, are as worried about the boundaries any more so long as the story takes us to strange new places.

This article originally appeared at TOR.com.

5 Comments